Transposit internship: IoT button prototype

My intern project this summer was to build an IoT button that can invoke APIs. It was the fullest stack: hardware, frontend, backend, infra.

On my first day as a Transposit intern, I was presented with a list of potential projects I could spend the summer working on. I had a week or so to decide, and there was some leeway; if I didn’t find any of them terribly interesting, we could tweak one to make it interesting, or even come up with something different. Luckily, I saw a few cool ideas on the list, and even one that seemed really cool: a "Transposit button."

The button#

The general idea was this: using the Transposit platform, developers can write applications that combine various APIs. Currently, they can run these apps a few different ways: interactively in the development console, via an HTTP request to an authenticated endpoint, or on a schedule as a recurring task. What if they could also run apps by pressing a physical IoT button?

I thought about some potential applications for a button like this. Imagine an operation you’d like to run frequently and easily, but there’s not a specific time each day you want to run it. For example, let’s say you discover music by listening to Spotify playlists over your Sonos. When you hear a song you like, you want to add it to your library. However, your phone might be in another room, and even if it’s right next to you, it’s annoying to open the app every time you hear a nice track. In Transposit, you could write a SQL operation that gets the song currently playing in your Spotify and adds it to your library, which might look like this:

SELECT * FROM spotify.save_track

WHERE ids IN (SELECT item.id FROM spotify.player_currently_playing)Then, you could just hit the button to run this operation whenever you hear something you like! Really cool stuff.

Project planning#

Next, I thought about what working on this project might actually look like. If we wanted to produce these buttons and give them to developers, it would have to be easy to grab a new button, connect it to WiFi, tie it to your Transposit account, and immediately start running operations with it.

The cool thing about this to me, beyond the inherent coolness of making things happen on the internet with a physical object, was how truly full-stack of a project it seemed. Enabling the whole setup and operation-calling procedure would involve significant work with Transposit’s frontend, backend, and cloud infrastructure, not to mention hardware code for the button itself.

When confronted with this technological breadth, I’ll admit I was a bit hesitant. "Maybe I should choose a project that deals with a smaller slice of the tech stack," I thought; after all, I’d never worked with hardware before, let alone anything AWS-related. The one thing pulling me in the other direction, giving me a little bit of hope that this project wouldn’t be too daunting, was how eager and supportive my mentor Yoko and the rest of the team was during that first week. If I was going to jump blindfolded into a pool of Arduino memory faults and Terraform plan errors, this at least seemed like a good place to do so.

Frontend, backend, flowcharts#

After committing to the button project, my next step was outlining how a user would set up their button, as well as getting more specific about the technical work each part would require. After completing that initial outline, I began implementing a basic setup interface on the frontend with React - after connecting the button to a wifi network, this is the page a developer will go to to link it with their account.

Next, I set up two API endpoints on the backend: one for this setup form to call to listen for a confirmation press, and one for the actual button to call to confirm that setup. I wanted to implement the interaction between these two endpoints using a pub/sub architecture, wherein the first endpoint subscribed to listen for the code inputted on the frontend, and the second endpoint published to that channel.

Before I went about doing this, Yoko had me draw up a visual flowchart for how this communication between the two endpoints would work. This wasn’t something I previously would have done on my own, but it really helped me explore all the different situations my system might encounter. Importantly, I realized that some cases I was planning on handling in my code would actually never happen, and also realized that I’d missed something: in my current design there was no way for a button to know if its setup press had been received by any listener (pub/sub messaging intentionally doesn’t include this). That half hour I spent drawing up this diagram saved me many more hours down the line that I would’ve spent implementing unnecessary features and retracing my steps to cover details I initially omitted.

This example gets at a larger point that I think is important for anyone completing a similar project, intern or otherwise. It would’ve been easy to finish my work quickly by just calling Yoko over to my desk whenever I hit a roadblock and asking her to tell me what the solution was. That also would have been a lot easier for her: telling someone “just use function x/library y” takes less time and effort than gradually helping them reach their own solution.

Coming from a college CS program, where one priority is just completing your assignments on time, I sometimes had to fight the instinct to ask point-blank for possible solutions. Case in point: our early Slack messages contain some moments where I ask “why isn’t this isn’t working?” and Yoko (thankfully) responds “well, where might be a good place to start looking?” It can be easy to get lazy, especially with smart, helpful people around you, so it’s important to remember to ask the right sorts of questions. That’s definitely not to say “don’t ask any questions” - quite the opposite - but you get a lot more out of “how should I go about solving this?” than “what’s the solution?,” as you might expect.

AWS, hardware, and more#

After getting the backend up and running, I moved on to writing an AWS Lambda function to receive HTTP requests from the physical button, paired with a DynamoDB table to keep track of button ownership. This was a good opportunity to learn more about AWS infrastructure and managing all the microservices it takes to build a modern web application.

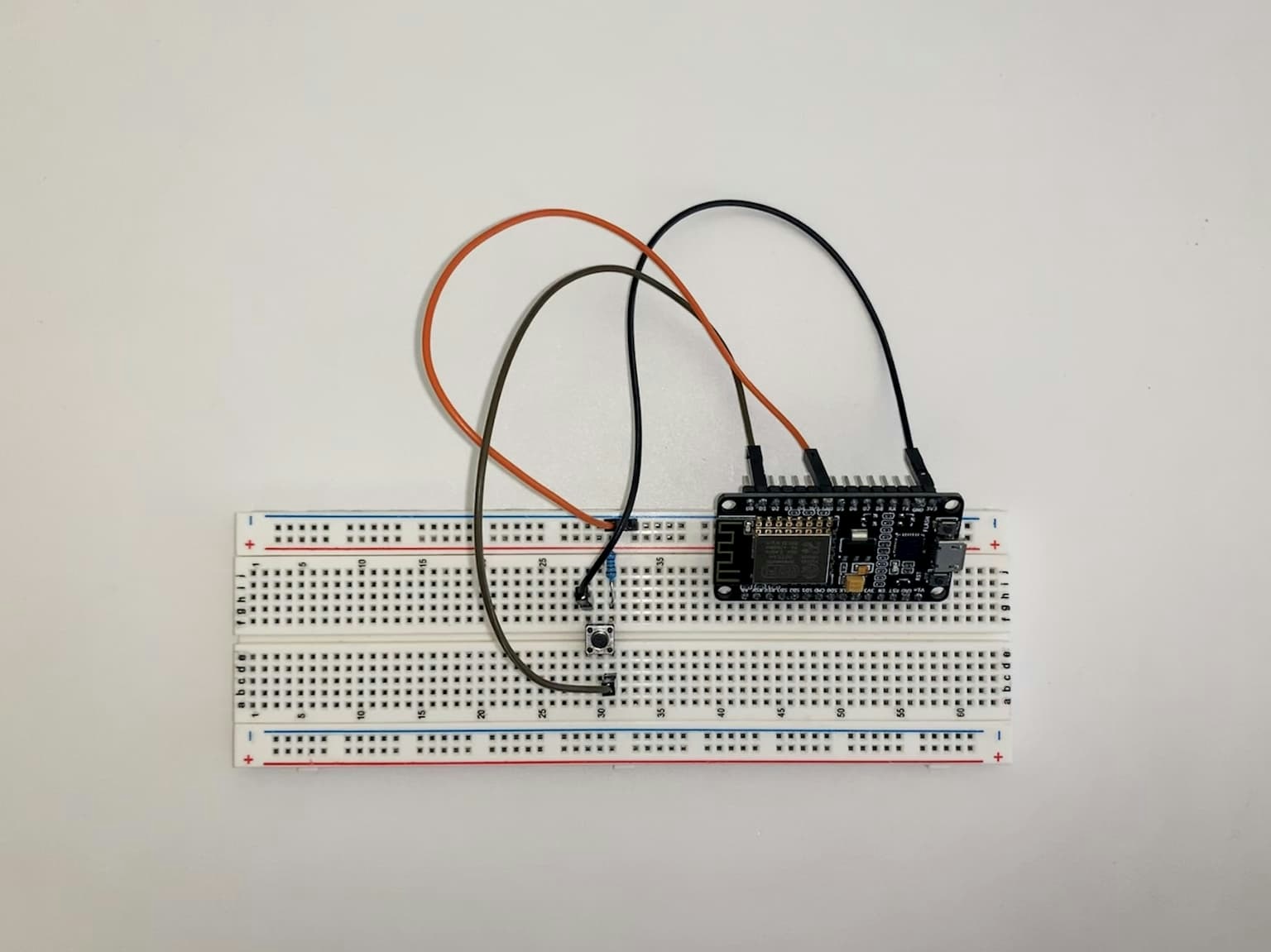

On the hardware side of things, I used an Arduino WiFi library so users could configure the button with their own network, and then did some more work to get it to send HTTP requests to the Lambda, while keeping track of whether it had been successfully set up with an account or not. Finally, I added some code to create a designated button application for the user during setup, and enabled subsequent presses to then run that application.

Each of these steps came with their own challenges and idiosyncrasies, similar to what I experienced with backend endpoints and pub/sub; I often spent a few days exploring and getting up to speed on a new part of the stack before doing any interesting work on it. This sort of project structure allowed me to experience a wide range of different software engineering problems - everything from broad Terraform infrastructure issues to the struggles of writing to a specific Arduino EEPROM memory address - which was really great for discovering common strategies I could use to aproach them instead of situation-specific tricks.

Some takeaways#

Evidently, I learned a ton over the course of this project. I gained a much clearer picture of the communication between an application’s frontend and backend. I learned more than I thought I ever could about HTTP requests and status codes (200 = Success, 400 = Client Error, 418 = I’m A Teapot). I learned a ton about Git, as having my own project branch off of master gave me the confidence to try ambitious rebase maneuvers I might not have tried otherwise.

I also - maybe most importantly - learned to spell the word “receive.” Early in the summer, I would try and call a “pressReceive” function I thought I had just written, only to discover the compiler couldn’t find it because I had actually created a function named “pressRecieve”. A few weeks of doing that was enough to make sure I never make that mistake again. Generally, the most consequential lessons happened when I didn’t know how to do something and saw how my coworkers might approach solving the same problem.

In closing, some people might be curious about my thoughts about interning at Transposit compared to other tech companies. It’d be easy to cite the lunches, location, office, and other perks as a major draw, because all of those things are really nice. I get the sense, though, that a lot of other tech companies provide similar benefits. The unique stuff to me, really, was the combination of 1) an interesting, cool product to work on (one that I would actually use if I didn’t work there) and 2) the interesting, cool people building it. It seemed like a lot of my other friends working at tech companies around the bay often had to compromise between working on a product they genuinely enjoyed and with people they genuinely enjoyed. I’m happy to report that at Transposit I got to experience both.

Jules Becker · Aug 20th, 2019

Jules Becker · Aug 20th, 2019